Well reasoned…

Category: Digital Economy

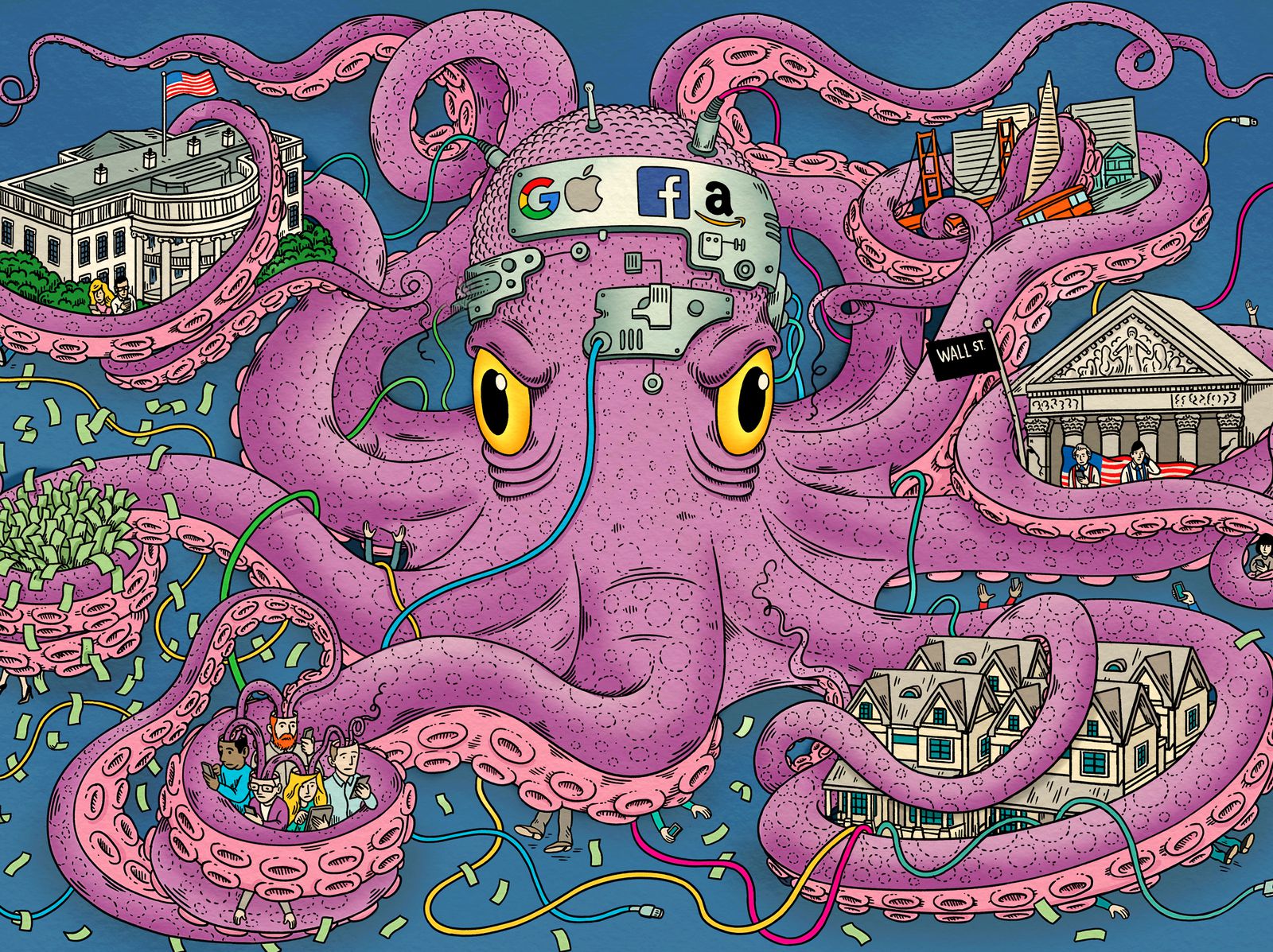

Dystopia

Antitrust and Vampire Squids

The US government wants to break up Facebook. Good – it’s long overdue

The Guardian, December 11, 2020

This week the government filed a ground-breaking antitrust suit against Facebook, seeking to break up the corporation for monopolistic practices. The suit comes on the heels of a similar case against Google, as well as an aggressive Democrat-authored congressional report recommending taking apart not just Google and Facebook, but Apple and Amazon as well.

The evidence against Facebook seems overwhelming, with enforcers pointing to internal email conversations in which the CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, and his colleagues allegedly conspired to monopolize the social media space by buying rivals and stifling competitors. Proof of intent to violate antitrust law appears to be ample. Yet news articles covering the case describe it as “far from a slam dunk”, and competition law experts predict that enforcers will “face an uphill battle” in proving their claims.

Embedded in these muted words about the legal viability of the case is a political battle about the nature of economic power. Both antitrust suits are the result of a new movement of anti-monopoly scholars and advocates pushing to reform a heavily concentrated and misshapen American economy. Yet within the cocooned world of orthodox antitrust experts, there’s a suspicious lack of enthusiasm for breaking up Facebook, or any of the tech goliaths. Fiona Scott Morton, for instance, a former Obama enforcer and opinion leader at Yale, wrote last year that “break-ups are not a good solution to the economic harms created by large firms in this sector.” And last year the leading antitrust scholar Herb Hovenkamp argued that “breakup remedies are radical and they frequently have unintended consequences,” and warned that “Judges aren’t good at breaking up companies.”

In this formulation, break-ups are a legally difficult and flawed remedy, akin to amputating the leg of someone in need of a pedicure. Some politicians are still listening to these experts; Republican politicians have expressed skepticism at break-ups, but even the 2020 Democratic platform says that regulators should only consider breaking up corporations “as a last resort”. More than politicians, judges listen to these arguments, and rewrite antitrust law from the bench to make bringing monopolization cases and winning them – even when the evidence is overwhelming – far too expensive and difficult.

Such a situation is historically unusual. As the historian Richard John notes, America has a long history of breaking up big companies. Some of those broken-up entities include logging companies in Maine in the 1840s, Standard Oil in the 1910s, and AT&T in the 1980s. In fact, in 1961 the supreme court pronounced that breaking up companies has “been called the most important of antitrust remedies. It is simple, relatively easy to administer, and sure.”

So what explains this modern reluctance?

The standard account is that a group of libertarian law and economics scholars in and around the University of Chicago recentered antitrust in the 1970s. These men, led by Milton Friedman, Robert Bork and George Stigler, sought to attack the New Deal regulatory state, and free concentrated capital. Bork led the legal crusade against what he called the “militant ideology” of aggressive antitrust enforcers. His goal was to pull control of this area of law out of the hands of liberal legislative bodies and place it in the hands of highly technical conservative economists and lifetime-appointed judges who would listen to them. When Ronald Reagan became president, he radically narrowed antitrust, amounting to what Bork called a “revolution in a major American policy”.

But this is only part of the story. It fails to explain how, in 2004, Antonin Scalia convinced his fellow supreme court justices, including Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, to join him in a unanimous supreme court decision which undermined the ability to bring monopolization cases by holding that the “charging of monopoly prices is not only not unlawful, it is an important element of the free-market system.

The liberal justices were swayed by a different set of scholars, less-well known in the revolution that has produced today’s monopoly-heavy economy. These scholars challenged Bork-influenced libertarians over certain methodological questions but accepted the ideological contention that antitrust should be a technical area without broader democratic goals.

This group is led by Hovenkamp, an academic centrist technocrat, who is the most important antitrust thinker alive today, nicknamed the “dean of the antitrust bar”. His partnership with Lyndon Johnson’s antitrust chief Don Turner and Harvard scholar Phil Areeda on a key antitrust treatise set the stage for his intellectual dominance in the 1980s. Stephen Breyer, a liberal justice and an adherent of Hovenkamp, once noted that advocates would rather have “two paragraphs of [the] treatise on their side than three courts of appeals or four supreme court justices.” Breyer wasn’t understating the point; to date, Hovenkamp has been cited by our highest court in 38 different cases, far more often than Bork.

Hovenkamp is an intellectual historian by training, and his views on antitrust policy are situated in a misleading narrative. His research radically downplays the historical importance of legislative and social movements focused on the democratic need to control big business, and instead emphasizes the role economists and technocrats began to play in shaping the law during the Gilded Age. As part of this narrative, he peddles an incomplete account of the origin of the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the most important piece of anti-monopoly legislation ever enacted by Congress. Hovenkamp argues that there is no evidence that the framers of the Sherman Act sought to curtail monopolies brought about as a result of “superior skill or industry”. According to Hovenkamp, US Congress – and by extension Americans in general – never had a problem with big corporations, or even monopolies; we just didn’t like it when those monopolies became predatory.

This elitist and technocratic framework glosses over our rich anti-monopoly tradition. Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and Frederick Douglass all opposed monopolies on political grounds, and state legislatures in the 19th century began breaking up companies almost as soon as they started issuing corporate charters. Senator Sherman himself explained that the purpose of the federal antitrust act was “to put an end to great aggregations of capital because of the helplessness of the individual before them.”

Judge Learned Hand, whose decisions in contract and corporate law are still read with reverence, laid out the basic federal antitrust framework which was endorsed by the supreme court in 1946 and 1968 and governed our economy for most of the 20th century. In mandating the breakup of the aluminum monopoly of Alcoa in 1945, Hand concluded that monopoly power, in and of itself, was illegal. He explained that the Sherman Act is a law prohibiting monopolies, full stop, no matter whether they are predatory. He pointed out that Congress updated the antitrust laws four times in the 20th century to hit back at courts who attempted to narrow them.

Antitrust theory is dominated by reactionary yet often wildly inconsistent thinkers. Hovenkamp, who for decades resisted any action to rein in large technology firms, argued a year ago that breaking up these giants would send the economy back to “the Stone Age”. This week, reversing his position, Hovenkamp conceded that breaking up Facebook is now warranted – revealing his entire school of thought as largely a reactionary force torn between bending to concentrated financial power and scandalous headlines of abusive market power.

It is encouraging that the government is seeking to break up Google and Facebook, and that policymakers are rejecting flawed legal theorizing. But the resistance to restoring our anti-monopoly tradition runs much deeper than Robert Bork and his rightwing legacy. As we’ve seen, it’s just as entrenched within the centrist academic and judicial citadels of well-meaning technocrats who carry a deeply ingrained fear of too much democratic influence over the economy.

Policymakers and judges are going to have to shake off the misleading narrative spun by the current antitrust establishment. Doing so is essential not only for supporting fair markets, but for preserving democracy itself.

Competition is essential, which requires open access to markets and transparency.

Censored

We need to be aware of the real threats of centralized control and bias over public information. This is the blueprint for an Orwellian society.

Break Up Big Tech

This needs to be done with a scalpel, not a hammer, but it needs to be done for many reasons. Not least of all for the massive transfer and concentration of wealth and power. Privacy is a private good, while information is a public good.

The Changing Nature of the Business

Bringing transparency to the music biz

More recently, artists of all stripes have gone after the new music gatekeepers: digital streaming platforms (Spotify purportedly pays $0.00437 a stream). For artists to secure better deals, they need transparency and information… this is exactly what CreateSafe is setting out to provide.

A Silver Lining.

Tech Anti-Trust Legislation

How “Breaking Up” Apple and Amazon Might Actually Work

by Will Oremus on Medium.

A banking law from 1956 offers a realistic model for regulating dominant internet platforms

Excerpt:

The Pattern

The antitrust assault on Big Tech is taking shape.

-

- Bipartisan recommendations for antitrust action against the tech giants could come as soon as September, Rep. David Cicilline, D-MA, told Bloomberg on Wednesday. Cicilline chairs the House antitrust subcommittee that has conducted a year-long antitrust investigation, including last month’s high-profile antitrust hearing. That hearing was the sixth in the ongoing probe, which is expected to culminate in a report to Congress.

- In an interview with Bloomberg TV’s Emily Chang, Cicilline got specific for the first time about what that report might say. The subcommittee is developing a “menu of options,” he said, that include updating old antitrust statutes aimed at oil and railroad monopolies; reforming federal antitrust agencies and making sure they have the resources to prosecute companies; and revitalizing private-sector enforcement.

- Most interestingly, he hinted at two potential pieces of legislation that would target the tech sector in particular. One would seek to enforce principles of portability and interoperability. The second, he said, would be more ambitious in scope: “a sort of Glass-Steagall of the internet, saying you can either be a platform or you can be a producer of goods and services. You cannot do both, because they’d be in conflict.”

- The Glass-Steagall Act, passed in 1933, required the separation of commercial banking from investment banking. It was crafted to address the conflicts of interest that arose when banks invested consumers’ assets in securities. The legislation divided financial institutions into investment banks such as Goldman Sachs and commercial banks such as Bank of America. Its 1999 repeal was cited by some economists as a precipitating factor in the 2008 financial crisis. A “Glass-Steagall of the internet,” in Cicilline’s analogy, would address the conflicts of interest that arise when companies that own dominant tech platforms also compete with the third parties who use those platforms.

- For instance, Apple presumably would no longer be allowed to both control iOS and offer services such as Apple Music that go head-to-head on iOS with rivals such as Spotify. Amazon might no longer be allowed to produce its own lines of clothing and household goods to rival those of third-party sellers on its site. (Its cloud division, Amazon Web Services, has similar issues.) Google, perhaps, would have to give up on services such as Google Shopping, which allegedly benefits from high placement in its own search results. It’s less clear to me which of Facebook’s existing products would run afoul of it, if any. Likely, Facebook’s social networking dominance would be targeted through some of the other mechanisms Cicilline mentioned; he specifically called its acquisition of Instagram “illegal.”

- At the risk of getting wonky, an even better analogy than Glass-Steagall might be the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, which banned banks from holding ownership stakes in non-banking industries. The concern was that bank holding companies could boost their own non-banking businesses over those of rivals with favorable loan terms, or nudge their loan clients to patronize their other businesses. That sounds a lot like how Apple, Amazon, and in some cases Google allegedly tilt their platforms to favor their own services.

- If this sort of legislation came to pass, the result would be a form of “breaking up Big Tech,” as some of the giants would likely be required to sell off or shutter some of their business lines. It echoes at least one part of Warren’s plan, which called for “large tech platforms to be designated as ‘Platform Utilities’ and broken apart from any participant on that platform.” Yet it would likely leave intact the core of each business, and would not necessarily require the tortuous untangling of, say, Apple’s hardware products from iOS, or Amazon.com from Amazon Web Services, which seems to be what some opponents of breakups have in mind. No doubt the details would still be tricky and heavily litigated. But they’d be unlikely to cripple the tech giants in the ways that would leave them unable to compete globally with Chinese rivals, which is a fear that the U.S. tech companies have been busy stoking.

- There are some persuasive arguments for going much farther than a Glass-Steagall or Bank Holding Company Act to rein in the internet’s behemoths. Longtime digital rights activist and blogger Cory Doctorow made the case for robust antitrust action in a new book published on OneZero this week, called How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism. The book is especially worth reading for anyone familiar with Shoshana Zuboff’s influential 2019 book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism, which Doctorow builds on and critiques. Zephyr Teachout’s book Break ’Em Up and Tim Wu’s book The Curse of Bigness are two other recent works that view size itself as the crux of the antitrust problem.

- But Cicilline’s comments to Bloomberg suggest that a full dismantling of Silicon Valley’s dominance is unlikely to be an outcome of the current investigation. That may disappoint critics such as Doctorow, Teachout, and Wu. At the same time, it should puncture the notion that breaking up Big Tech is something to be feared — at least, by anyone other than the tech giants themselves.

Q: How Can a Musician Make Money?

Q: What do musicians do?

A: Create and share their art!

Q: How does a musician make money?

A: Money?

Hint: It’s all about the data.

Why You Should You Get Paid for Your Data

Why You Should You Get Paid for Your Data

Seven out of the top 10 most valuable companies in the world are tech companies that either directly generate profit from data or are empowered by data from the core. Multiple surveys show that the vast majority of business decision makers regard data as an essential asset for success. We have all experienced how data is shifting this major paradigm shift for our personal, economic and political lives. Whoever owns the data owns the future.

But who’s producing the data? I assume everyone in this room has a smartphone, several social media accounts and has done a Google search or two in the past week. We are all producing the data.