They don’t. They just don’t hear it enough in the right context!

This is the problem tuka is trying to solve: to recreate that music sharing network you had when you were in high school and college!

The Conversation.

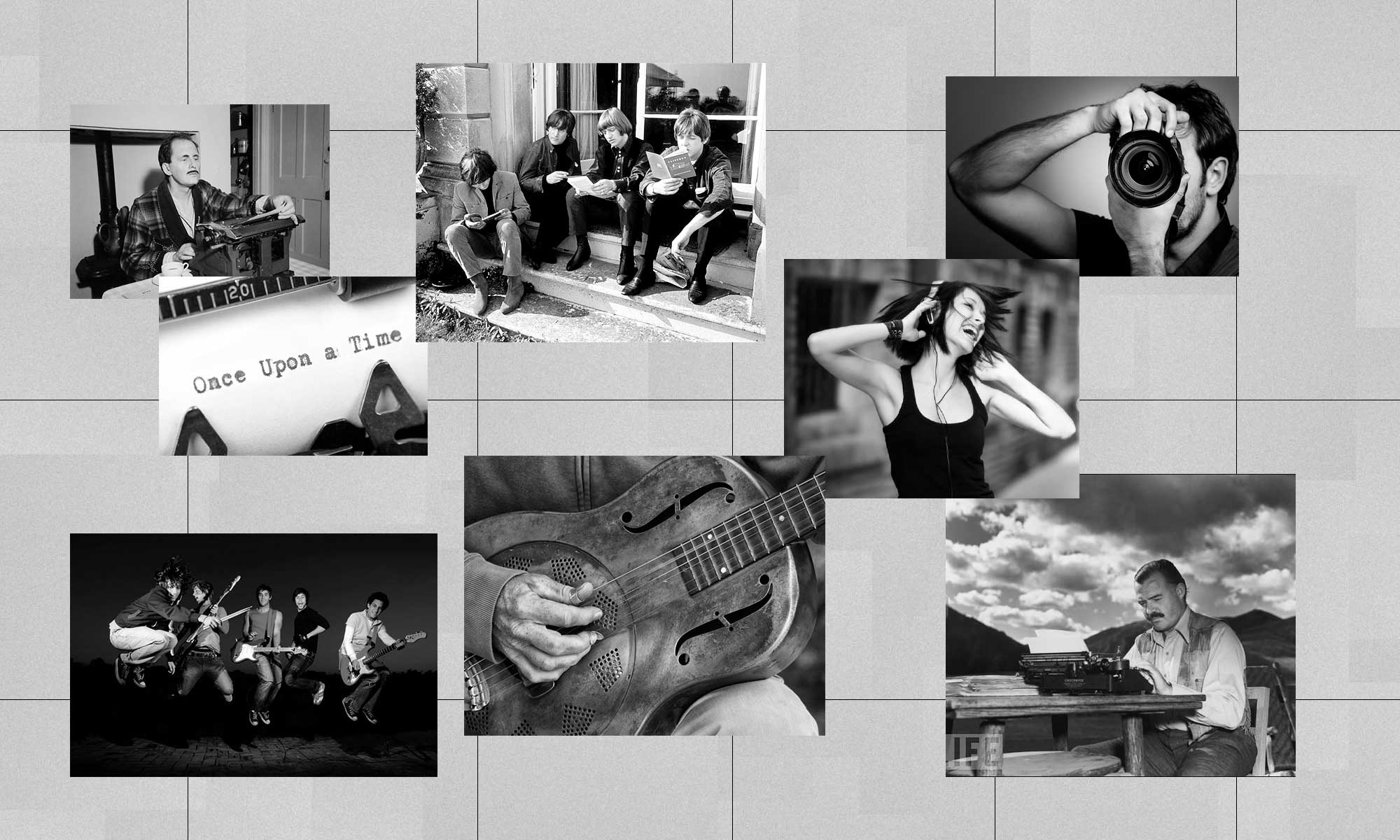

Why do old people hate new music?

by Frank T. McAndrew

When I was a teenager, my dad wasn’t terribly interested in the music I liked. To him, it just sounded like “a lot of noise,” while he regularly referred to the music he listened to as “beautiful.”

This attitude persisted throughout his life. Even when he was in his 80s, he once turned to me during a TV commercial featuring a 50-year-old Beatles tune and said, “You know, I just don’t like today’s music.”

It turns out that my father isn’t alone.

As I’ve grown older, I’ll often hear people my age say things like “they just don’t make good music like they used to.”

Why does this happen?

Luckily, my background as a psychologist has given me some insights into this puzzle.

We know that musical tastes begin to crystallize as early as age 13 or 14. By the time we’re in our early 20s, these tastes get locked into place pretty firmly.

In fact, studies have found that by the time we turn 33, most of us have stopped listening to new music. Meanwhile, popular songs released when you’re in your early teens are likely to remain quite popular among your age group for the rest of your life.

There could be a biological explanation for this. There’s evidence that the brain’s ability to make subtle distinctions between different chords, rhythms and melodies gets worse with age. So to older people, newer, less familiar songs might all “sound the same.”

But I believe there are some simpler reasons for older people’s aversion to newer music. One of the most researched laws of social psychology is something called the “mere exposure effect.” In a nutshell, it means that the more we’re exposed to something, the more we tend to like it.

This happens with people we know, the advertisements we see and, yes, the songs we listen to.

When you’re in your early teens, you probably spend a fair amount of time listening to music or watching music videos. Your favorite songs and artists become familiar, comforting parts of your routine.

For many people over 30, job and family obligations increase, so there’s less time to spend discovering new music. Instead, many will simply listen to old, familiar favorites from that period of their lives when they had more free time.

Of course, those teen years weren’t necessarily carefree. They’re famously confusing, which is why so many TV shows and movies – from “Glee” to “Love, Simon” to “Eighth Grade” – revolve around the high school turmoil.

Psychology research has shown that the emotions that we experience as teens seem more intense than those that comes later. We also know that intense emotions are associated with stronger memories and preferences. All of this might explain why the songs we listen to during this period become so memorable and beloved.

So there’s nothing wrong with your parents because they don’t like your music. In a way, it’s all part of the natural order of things.

At the same time, I can say from personal experience that I developed a fondness for the music I heard my own children play when they were teenagers. So it’s certainly not impossible to get your parents on board with Billie Eilish and Lil Nas X.