From Hillsdale College’s Imprimus:

Who Is in Control? The Need to Rein in Big Tech

Allum Bokhari

The following is adapted from a speech delivered at Hillsdale College on November 8, 2020, during a Center for Constructive Alternatives conference on Big Tech.

In January, when every major Silicon Valley tech company permanently banned the President of the United States from its platform, there was a backlash around the world. One after another, government and party leaders—many of them ideologically opposed to the policies of President Trump—raised their voices against the power and arrogance of the American tech giants. These included the President of Mexico, the Chancellor of Germany, the government of Poland, ministers in the French and Australian governments, the neoliberal center-right bloc in the European Parliament, the national populist bloc in the European Parliament, the leader of the Russian opposition (who recently survived an assassination attempt), and the Russian government (which may well have been behind that attempt).

Common threats create strange bedfellows. Socialists, conservatives, nationalists, neoliberals, autocrats, and anti-autocrats may not agree on much, but they all recognize that the tech giants have accumulated far too much power. None like the idea that a pack of American hipsters in Silicon Valley can, at any moment, cut off their digital lines of communication.

I published a book on this topic prior to the November election, and many who called me alarmist then are not so sure of that now. I built the book on interviews with Silicon Valley insiders and five years of reporting as a Breitbart News tech correspondent. Breitbart created a dedicated tech reporting team in 2015—a time when few recognized the danger that the rising tide of left-wing hostility to free speech would pose to the vision of the World Wide Web as a free and open platform for all viewpoints.

This inversion of that early libertarian ideal—the movement from the freedom of information to the control of information on the Web—has been the story of the past five years.

***

When the Web was created in the 1990s, the goal was that everyone who wanted a voice could have one. All a person had to do to access the global marketplace of ideas was to go online and set up a website. Once created, the website belonged to that person. Especially if the person owned his own server, no one could deplatform him. That was by design, because the Web, when it was invented, was competing with other types of online services that were not so free and open.

It is important to remember that the Web, as we know it today—a network of websites accessed through browsers—was not the first online service ever created. In the 1990s, Sir Timothy Berners-Lee invented the technology that underpins websites and web browsers, creating the Web as we know it today. But there were other online services, some of which predated Berners-Lee’s invention. Corporations like CompuServe and Prodigy ran their own online networks in the 1990s—networks that were separate from the Web and had access points that were different from web browsers. These privately-owned networks were open to the public, but CompuServe and Prodigy owned every bit of information on them and could kick people off their networks for any reason.

In these ways the Web was different. No one owned it, owned the information on it, or could kick anyone off. That was the idea, at least, before the Web was captured by a handful of corporations.

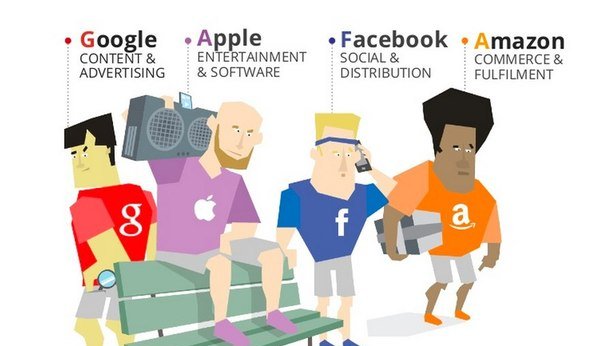

We all know their names: Google, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, Amazon. Like Prodigy and CompuServe back in the ’90s, they own everything on their platforms, and they have the police power over what can be said and who can participate. But it matters a lot more today than it did in the ’90s. Back then, very few people used online services. Today everyone uses them—it is practically impossible not to use them. Businesses depend on them. News publishers depend on them. Politicians and political activists depend on them. And crucially, citizens depend on them for information.

Today, Big Tech doesn’t just mean control over online information. It means control over news. It means control over commerce. It means control over politics. And how are the corporate tech giants using their control? Judging by the three biggest moves they have made since I wrote my book—the censoring of the New York Post in October when it published its blockbuster stories on Biden family corruption, the censorship and eventual banning from the Web of President Trump, and the coordinated takedown of the upstart social media site Parler—it is obvious that Big Tech’s priority today is to support the political Left and the Washington establishment.

Big Tech has become the most powerful election-influencing machine in American history. It is not an exaggeration to say that if the technologies of Silicon Valley are allowed to develop to their fullest extent, without any oversight or checks and balances, then we will never have another free and fair election. But the power of Big Tech goes beyond the manipulation of political behavior. As one of my Facebook sources told me in an interview for my book: “We have thousands of people on the platform who have gone from far right to center in the past year, so we can build a model from those people and try to make everyone else on the right follow the same path.” Let that sink in. They don’t just want to control information or even voting behavior—they want to manipulate people’s worldview.

Is it too much to say that Big Tech has prioritized this kind of manipulation? Consider that Twitter is currently facing a lawsuit from a victim of child sexual abuse who says that the company repeatedly failed to take down a video depicting his assault, and that it eventually agreed to do so only after the intervention of an agent from the Department of Homeland Security. So Twitter will take it upon itself to ban the President of the United States, but is alleged to have taken down child pornography only after being prodded by federal law enforcement.

***

How does Big Tech go about manipulating our thoughts and behavior? It begins with the fact that these tech companies strive to know everything about us—our likes and dislikes, the issues we’re interested in, the websites we visit, the videos we watch, who we voted for, and our party affiliation. If you search for a Hannukah recipe, they’ll know you’re likely Jewish. If you’re running down the Yankees, they’ll figure out if you’re a Red Sox fan. Even if your smart phone is turned off, they’ll track your location. They know who you work for, who your friends are, when you’re walking your dog, whether you go to church, when you’re standing in line to vote, and on and on.

As I already mentioned, Big Tech also monitors how our beliefs and behaviors change over time. They identify the types of content that can change our beliefs and behavior, and they put that knowledge to use. They’ve done this openly for a long time to manipulate consumer behavior—to get us to click on certain ads or buy certain products. Anyone who has used these platforms for an extended period of time has no doubt encountered the creepy phenomenon where you’re searching for information about a product or a service—say, a microwave—and then minutes later advertisements for microwaves start appearing on your screen. These same techniques can be used to manipulate political opinions.

I mentioned that Big Tech has recently demonstrated ideological bias. But it is equally true that these companies have huge economic interests at stake in politics. The party that holds power will determine whether they are going to get government contracts, whether they’re going to get tax breaks, and whether and how their industry will be regulated. Clearly, they have a commercial interest in political control—and currently no one is preventing them from exerting it.

To understand how effective Big Tech’s manipulation could become, consider the feedback loop.

As Big Tech constantly collects data about us, they run tests to see what information has an impact on us. Let’s say they put a negative news story about someone or something in front of us, and we don’t click on it or read it. They keep at it until they find content that has the desired effect. The feedback loop constantly improves, and it does so in a way that’s undetectable.

What determines what appears at the top of a person’s Facebook feed, Twitter feed, or Google search results? Does it appear there because it’s popular or because it’s gone viral? Is it there because it’s what you’re interested in? Or is there another reason Big Tech wants it to be there? Is it there because Big Tech has gathered data that suggests it’s likely to nudge your thinking or your behavior in a certain direction? How can we know?

What we do know is that Big Tech openly manipulates the content people see. We know, for example, that Google reduced the visibility of Breitbart News links in search results by 99 percent in 2020 compared to the same period in 2016. We know that after Google introduced an update last summer, clicks on Breitbart News stories from Google searches for “Joe Biden” went to zero and stayed at zero through the election. This didn’t happen gradually, but in one fell swoop—as if Google flipped a switch. And this was discoverable through the use of Google’s own traffic analysis tools, so it isn’t as if Google cared that we knew about it.

Speaking of flipping switches, I have noted that President Trump was collectively banned by Twitter, Facebook, Twitch, YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat, and every other social media platform you can think of. But even before that, there was manipulation going on. Twitter, for instance, reduced engagement on the President’s tweets by over eighty percent. Facebook deleted posts by the President for spreading so-called disinformation.

But even more troubling, I think, are the invisible things these companies do. Consider “quality ratings.” Every Big Tech platform has some version of this, though some of them use different names. The quality rating is what determines what appears at the top of your search results, or your Twitter or Facebook feed, etc. It’s a numerical value based on what Big Tech’s algorithms determine in terms of “quality.” In the past, this score was determined by criteria that were somewhat objective: if a website or post contained viruses, malware, spam, or copyrighted material, that would negatively impact its quality score. If a video or post was gaining in popularity, the quality score would increase. Fair enough.

Over the past several years, however—and one can trace the beginning of the change to Donald Trump’s victory in 2016—Big Tech has introduced all sorts of new criteria into the mix that determines quality scores. Today, the algorithms on Google and Facebook have been trained to detect “hate speech,” “misinformation,” and “authoritative” (as opposed to “non-authoritative”) sources. Algorithms analyze a user’s network, so that whatever users follow on social media—e.g., “non-authoritative” news outlets—affects the user’s quality score. Algorithms also detect the use of language frowned on by Big Tech—e.g., “illegal immigrant” (bad) in place of “undocumented immigrant” (good)—and adjust quality scores accordingly. And so on.

This is not to say that you are informed of this or that you can look up your quality score. All of this happens invisibly. It is Silicon Valley’s version of the social credit system overseen by the Chinese Communist Party. As in China, if you defy the values of the ruling elite or challenge narratives that the elite labels “authoritative,” your score will be reduced and your voice suppressed. And it will happen silently, without your knowledge.

This technology is even scarier when combined with Big Tech’s ability to detect and monitor entire networks of people. A field of computer science called “network analysis” is dedicated to identifying groups of people with shared interests, who read similar websites, who talk about similar things, who have similar habits, who follow similar people on social media, and who share similar political viewpoints. Big Tech companies are able to detect when particular information is flowing through a particular network—if there’s a news story or a post or a video, for instance, that’s going viral among conservatives or among voters as a whole. This gives them the ability to shut down a story they don’t like before it gets out of hand. And these systems are growing more sophisticated all the time.

***

If Big Tech’s capabilities are allowed to develop unchecked and unregulated, these companies will eventually have the power not only to suppress existing political movements, but to anticipate and prevent the emergence of new ones. This would mean the end of democracy as we know it, because it would place us forever under the thumb of an unaccountable oligarchy.

The good news is, there is a way to rein in the tyrannical tech giants. And the way is simple: take away their power to filter information and filter data on our behalf.

All of Big Tech’s power comes from their content filters—the filters on “hate speech,” the filters on “misinformation,” the filters that distinguish “authoritative” from “non-authoritative” sources, etc. Right now these filters are switched on by default. We as individuals can’t turn them off. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

The most important demand we can make of lawmakers and regulators is that Big Tech be forbidden from activating these filters without our knowledge and consent. They should be prohibited from doing this—and even from nudging us to turn on a filter—under penalty of losing their Section 230 immunity as publishers of third party content. This policy should be strictly enforced, and it should extend even to seemingly non-political filters like relevance and popularity. Anything less opens the door to manipulation.

Our ultimate goal should be a marketplace in which third party companies would be free to design filters that could be plugged into services like Twitter, Facebook, Google, and YouTube. In other words, we would have two separate categories of companies: those that host content and those that create filters to sort through that content. In a marketplace like that, users would have the maximum level of choice in determining their online experiences. At the same time, Big Tech would lose its power to manipulate our thoughts and behavior and to ban legal content—which is just a more extreme form of filtering—from the Web.

This should be the standard we demand, and it should be industry-wide. The alternative is a kind of digital serfdom. We don’t allow old-fashioned serfdom anymore—individuals and businesses have due process and can’t be evicted because their landlord doesn’t like their politics. Why shouldn’t we also have these rights if our business or livelihood depends on a Facebook page or a Twitter or YouTube account?

This is an issue that goes beyond partisanship. What the tech giants are doing is so transparently unjust that all Americans should start caring about it—because under the current arrangement, we are all at their mercy. The World Wide Web was meant to liberate us. It is now doing the opposite. Big Tech is increasingly in control. The most pressing question today is: how are we going to take control back?